On July 1st 2006 the eyes of the world fell upon the Somme area of France, as we remembered the 1st day of the Battle of the Somme, a black day in the history of the twentieth century. There were ceremonies both official and unofficial throughout the region to pay respect to the thousands of men who paid the ultimate price on that day.

Little wonder then, perhaps, that 30th June has slipped past largely unnoticed for the last eighty-nine years. Yet that day held great significance for the people of Sussex, for the 30th of June became known as

“The day Sussex died.”

Between the towns of Bethune and Armentieres, in the Pas de Calais, lies Richebourg l’Avoue. Richebourg is surrounded by other villages and small towns, some with slightly more familiar names, at least to those with an interest in the Great War. Aubers, Festubert, and Neuve Chapelle are just some of the scenes of battles fought in 1915. Mention Richebourg to many people and their response is an unknowing look or a shrug of the shoulders. Yet Richebourg played a significant, if somewhat dubious, role in the Battle of the Somme, and an infamous one in the history of Lowther’s Lambs, officially the 11th, 12th and 13th (Southdowns) Battalions of The Royal Sussex Regiment.

The Battle of the Boar’s Head, Richebourg l’Avoue, was planned as a diversionary action to make the German Command believe that this area of the Pas de Calais was the one chosen for the major offensive of 1916. The intention was to prevent the Germans from moving troops to the Somme area, some fifty kilometres to the south.

British troops had been fighting in the area since 1914. The 2nd and 5th Battalions of The Royal Sussex, had fought at Richebourg during the Battle of Aubers Ridge, in May 1915, and in June of 1916 came the turn of the three Southdowns Battalions, which together formed the 116th (Southdowns) Brigade of the 39th Division, which had arrived in France on March 5th, 1916, taking over trenches in the Fleurbaix sector on March 20th.

On the 11th of June, the three Battalions went to the Divisional Reserve, being billeted around Locon, and commenced training for an attack (though this was still only a rumour). On June 16th they returned to the front line trenches in the Ferme du Bois area near Richebourg, holding the line until June 23rd, when news was received that the 39th Division were to make an attack on the Boar’s Head, a salient of the German lines, and that the 116th Brigade, the Southdowners, had been chosen to lead the attack. Further training followed. A replica of the battlefield had been built behind the lines, but the battalions had only days, not weeks, to consider it.

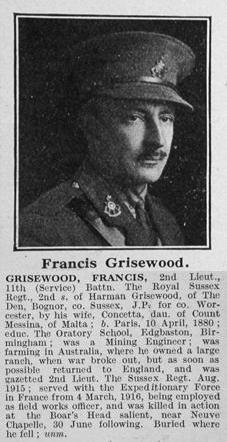

Initial plans had been that the 11th Battalion should lead the attack, with the 12th on their right, and the 13th in reserve. At the time that these orders were received, Lieutenant Colonel Harman Grisewood, was the Commanding Officer of the 11th (1st Southdowns). Grisewood had lost his brother George, the Adjutant of the 11th Battalion until March 1916, who died of illness, his obituary says of pneumonia, though Neville Lytton states meningitis, at Merville on March 27th 1916. His death had deeply affected Colonel Grisewood, who, it is said, on seeing the plans, was concerned that if his untried troops attacked over unfamiliar ground a disaster might result, and is said to have informed his brigade commander

” I am not sacrificing my men as cannon-fodder!”1

Needless to say the attack had to go in, but the Divisional Commander, Major General R. Dawson, aware of Grisewood’s comments, was concerned that this might be passed down to the men of the 11th Battalion, and so the roles of the 11th and 13th Battalions were reversed.

According to a letter from Col. Grisewood to Captain Neville Lytton, Grisewood was told to “clear off at once”.

Colonel Grisewood was succeeded by Major G H Harrison (the regular soldier).

Grisewood’s second brother Francis was to become a casualty of the Boar’s Head.

In consequence it was the 12th and 13th Battalions, with half the 11th supplying carrying parties, who made final preparations on 29th June, then assembled in the trenches of the Richebourg sector in the early hours of 30th June for the forthcoming attack, which was designed to “bite off the German position known as the Boar’s Head”, making the Germans believe that the real offensive was here, not the Somme.

At 2.50 am the preliminary bombardment commenced, final preparations were made, and scaling ladders were placed against the trench sides to allow the men to go “over the top”.

In his history of the regiment Martineau writes:

“The records of one battalion are liable to be more eloquent than those of another. Yet, with the Southdown Brigade in France, there is much in common, and, in that sense, one may be taken to speak for all. There were superficial differences, however.

Thus, the 11th Battalion, while supplying carrying-parties for the 12th and 13th on the day of the Richebourg and Ferme du Bois assault, sustained 116 casualties in this service alone. The 12th Battalion, assembling in the front line at Ferme du Bois, while the artillery bombarded the enemy trenches, attacked at 3.05 am., on June 30th, seized the front line, which they held for four hours against considerably superior German forces, and even broke through to the support line, which they held for half an hour.

Naturally it could not last. The Germans were ready. There is even a story that one man brought back a notice in English, announcing: “Come on, Sussex boys. We’ve been waiting for you for three days!”

A heavy barrage on the front line and communication trenches prevented reinforcements from being sent forward, the supply of bombs and ammunition gave out, and the valiant survivors were compelled to withdraw. The Battalion’s 429 casualties included 17 officers.”

The War Diary of the 13th Battalion gives a more detailed account of the attack

“FERME DU BOIS. The battalion assembled at 1.30 am. On the morning of the 30th June in readiness for the assault, with all four platoons of each coy in the front line.

The preliminary bombardment on the morning of the attack opened at 2.50 am., and at 3.05 the leading wave of the battalion scaled the parapet, the remainder following at 50 yards interval. At the same time the flank attack under Lts. Whitley and Ellis gained a footing in the enemy trench. The passage across NO MAN’S LAND was accomplished with few casualties except in the left companies, which came under very heavy machine gun fire.

The two right companies succeeded in reaching their objective, but the two left companies only succeeded in penetrating the enemy’s wire in one or two places.

Just at this moment a smoke cloud, which was originally designed to mask our advance, drifted right across the front and made it impossible to see more than a few yards ahead. This resulted in all direction being lost and the attack devolving into small bodies of men not knowing which way to go.

Some groups succeeded in entering the support line, engaging the enemy with bombs and bayonet, and organizing the initial stages of a defence.

Other parties swung off to the right and entered the trench where the flank party was operating, causing a great deal of congestion.

On the left, the smoke and darkness made the job of penetrating the enemy wire so difficult that few, if any, succeeded in reaching the enemy support line, where they were subjected to an intense bombardment of HE. and whizz-bangs.

Capt. Hughes, who was wounded, seeing that his company was in danger of being cut off, gave the order for the evacuation of the enemy trenches, and the remainder of the attacking force returned to our trenches.

The enemy, who was evidently thoroughly prepared, now concentrated his energies on the front line, and, for the space of about 2½ hours, our front and support lines were subjected to an intense bombardment with heavy and light shells, causing a large number of casualties . . . The enemy casualties are also considered to have been considerable, large numbers of dead being seen in the enemy trenches.”

During the attack, the majority of Officers were killed or wounded, platoons, if not companies being led by NCOs.

Probably the best remembered of these was Company Sergeant Major Nelson Victor Carter, age 29, of Eastbourne in Sussex. CSM Carter, “A” Company, 12th Battalion, took the fourth wave into action under heavy shell and machine gun fire. Bombing matches took place, but after heavy casualties were suffered the men were forced to withdraw.

CSM Carter attacked a machine gun post which was causing particular trouble, shot one, or more, of the crew with his pistol before, apparently, turning the machine gun on the Germans. This bought much needed time to withdraw safely, and with this having been done Carter finally left the position.

The action in the support line had lasted only thirty minutes. CSM Carter continued to aid in the withdrawal to the first line, and later in the day, whilst bringing in the wounded, was shot in the chest, dying almost immediately . For his actions that day CSM Carter was awarded the Victoria Cross. The Citation read as follows:

London Gazette, 9 September 1916,

Boar’s Head, Richebourg l’Avoué, France, 30 June 1916, Company Sergeant-Major Nelson Victor Carter, 4th Company, 12th Bn., Royal Sussex Regiment.“For most conspicuous bravery. During an Attack he was in command of the fourth wave of the assault. Under intense shell and machine gun fire he penetrated, with a few men, into the enemy’s second line and inflicted heavy casualties with bombs. When forced to retire to the enemy’s first line, he captured a machine gun and shot the gunner with his revolver. Finally, after carrying several wounded men into safety, he was himself mortally wounded and died in a few minutes. His conduct throughout the day was magnificent.”

The following is a part of a letter written by Lieutenant (later Lt. Col.) Howard Robinson, Carter’s Company Commander to Kathleen Carter, Nelson’s wife.

“When I last saw him he was close to the German line, acting as leader to a small party of four or five men. I was afterwards told that he had entered the German second line, and had brought back an enemy machine gun, having put the gun team out of action. I heard that he shot one them with his revolver. I next saw him about an hour later (I had been wounded in the meanwhile and was lying in our trench). Your husband repeatedly went over the parapet. I saw him going over alone and carrying in our wounded men from ‘No Man’s Land’. He brought them in on his back, and he could not have done this had he not possessed exceptional physical strength as well as courage. It was in going over for the sixth or seventh time that the was shot through the chest. I saw him fall just inside our trench.

Somebody told me that about a month previously your husband carried a man about 400 yards across the open under machine gun fire and brought him safely into our trench. For this act I recommended him for the Military Cross. On every occasion, no matter how tight the hole we were in, he was always cheerful and hopeful, and never spared any pains to make the men comfortable and keep them cheery.”

Company Sergeant Nelson Carter is buried in the Royal Irish Rifles Cemetery, Laventie, France.

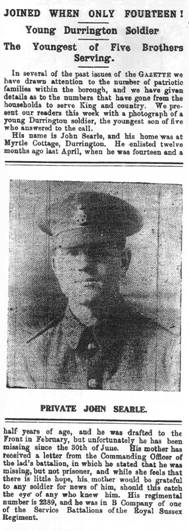

Also in action that day, with “B” Company, 12th Bn, was Private SD/2389 John Searle of Worthing. The youngest of five brothers, Pte Searle was just fourteen and a half years of age when he enlisted in April 1915, and had not reached his sixteenth birthday when he took part in the Battle of the Boar’s Head.

Private Searle is remembered on the Loos Memorial to the missing. He was amongst those whose bodies were never recovered after the battle.

Among the rare poetic spirits to be found among those who officered these battalions was Edmund Blunden. His Undertones of War contains impressions of the life lived by the men, and of the men themselves, which are intensely revealing. Concerning the Richebourg diversion, he wrote

“What the Brigade felt was summed up by some sentry who, asked by the General next morning what he thought of the attack, answered in the roundest fashion, ‘Like a butcher’s shop.’ Our own trenches had been knocked silly, and all the area of the attack had been turned into an Aceldama.”2

The Battle of the Boar’s Head lasted less than five hours.

The Southdowns Brigade lost 17 officers and 349 men killed.

Over 1000 were wounded or taken prisoner.

The 13th Battalion was all but wiped out.

Thanks to the Mayors of Richebourg and Aubers a commemoration of the sacrifice made by those men was held at Richebourg St. Vaast Cemetery on 30th June 2006.

Also on June 30th 2006

Group members laid wreaths at the Loos Memorial,

and CSM Carter’s grave in the Royal Irish Rifles Cemetery at Laventie.

Since the ninetieth anniversary we have remembered them.

We will endeavour to continue to do so at Richebourg St. Vaast Post Military Cemetery

At 17.00hrs on the last Saturday in June each year until the 100th anniversary, thereafter it will be the closest Saturday to 30th June.

“The 100th Anniversary Commemoration will be held at 17.00hrs on 30th June 2016.

God willing we will be there.”John Baines

*Edit – Although John Baines was not with us Gary Baines, his son, and family ensured that those brave boys were remembered on 30th June 2016 at 17:00.

For a link to the Centenary Commemoration photos, please click here

The major Boar’s Head Cemeteries are:

This piece draws on information from the Regimental Archive of The Royal Sussex Regiment held at the West Sussex County Council Records Office at Chichester, including a draft research document by Paul Reed, the War Diaries of the 11th , 12th, and 13th Battalions The Royal Sussex Regiment, and various letters written to the family of CSM Nelson Carter. Other sources include “A History of The Royal Sussex Regiment, 1701-1953” by Captain G. D. Martineau, and A Short History of The Royal Sussex Regiment (35th Foot – 107th Foot), from 1701 to 1926.